There is no such thing as one single true “design thinking”, and what complexity has to do with it.

Hi everyone, Kevin here.

A quick reflection on Design Thinking and why I disagree with most of today’s use of the concept.

And yes, I know what it sounds like but, please, bear with me: what I’m going at is probably the most common misunderstanding in the field. But first, let me clarify something: yes, you can find a somewhat “standard” definition of Design Thinking from some authorities.

It does not prevent practitioners to disagree on terms like process, stages, phases, steps, methodology, method, etc.

So, is Design Thinking a process? Or is it a “way to think”? Or is it a method? Do we have to pass through all the steps? Or are they stages? Phases?Well, it depends… right?

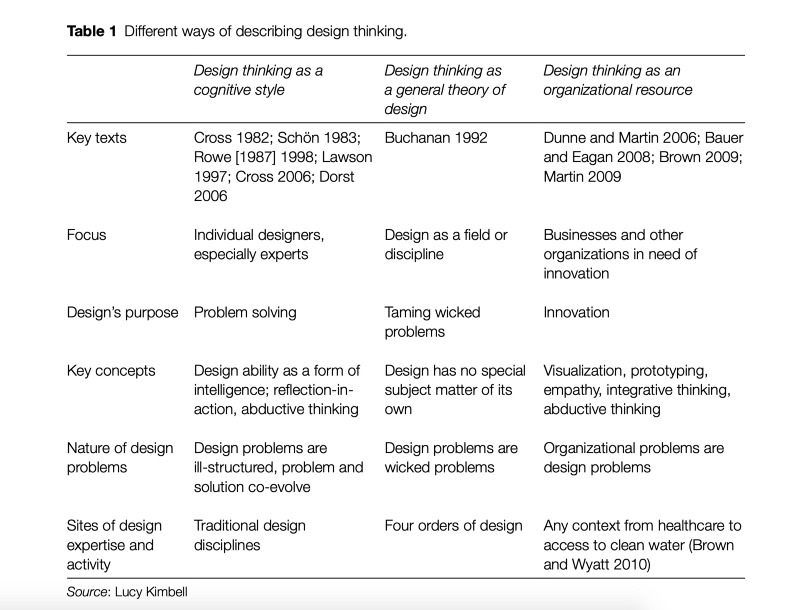

My point is that people really mean different things when they talk about Design Thinking. In practice, Design Thinking is not a standardized approach, nor a clearly defined body of knowledge, despite what one might think. From its origins to its current mainstream use, the approach evolved and mutated following its various appropriations as well as the evolution and specialization of the design practices.

Because of this, and its inherent adaptiveness, this made the concept easily permeable to other concepts. For instance, the Business appropriation of the Design Thinking added notions from the consumer, marketing, economics, and management theories (as taught in business schools). The appropriation of the approach in the “recent” technology-as-product field merged it with concepts from engineering and manufacturing –although it’s not the first occurrence.

Logically one might think that the true, untouched, “Design Thinking” lies somewhere in the past and it’s up to anyone to reconnect with it. But much like with religions and some recent appeal to nature, how do you determine what makes the true one truer than the others? How far should you look in history? How do you mitigate the most probable misalignment between this pure, original version, and our current reality and its dire contemporary challenges? And by doing so, don’t you alter its purity?

This is simply dumb reasoning, and history is on my side on this.

To be honest, I don’t think such a thing really exists apart from our desired and idealized idea of what could have been the original version, from our today’s point of view. It is, to me, a vain quest for “perfection” or “purity” that in some cases dangerously flirts with over-conservatism, radicalism, extremism, and change denial. This is also, in many instances, a demonstrable lack of understanding of field reality.

Personally, I see here the irony of the situation.

Built-up Tension

Most reactions and behaviors –either search for an “original truth” or disagreement on the definition– reveals interesting tensions that exist between different influences and realities within the same field. In other words, these tensions show a more multi-dimensional and transversal aspect of the broader definition of what we call “Design” today.

Conflicting theories, ideologies, and worldviews colliding together and from which emerges various, and diversified understandings. I think that we should probably, more than anyone else, accept this diversity instead of rejecting it. Note that acceptance does not mean taking everything for granted, and this should not prevent us to discuss, combine, merge, or eventually dismiss/remove some concepts. But doing it mindfully is different than blind & ignorant rejection.

But the design field does not really work like this. We do not build on each other knowledge in an efficient manner. The design world is much more built on hegemonic paradigms than, say, the scientific process. And it’s even without talking about the designers’ need for strong authoritative figures along with their ideas –a recurring pattern. Anyways.

Same words, different meanings.

These tensions reflect what you can realize when you start study complexity & systems theories, that different realities (contexts) imply different degrees of complexity, hence the sometimes inaudible critics made against this or that approach: this is the multi-dimensionality I talked about earlier. I am, sometimes, guilty of this oversimplification, as you probably are too.

Yes, some approaches are linear or too simplistic. So, what?

Let’s be honest, the problem does not lie here: you don’t have to always approach everything in a systemic, complex manner. There are plenty of instances where these approaches suffice.

Instead, the issue lies when not always well-informed practitioners try to fit a certain approach to all challenges. This is true on both sides of this continuum.

The Space-for-action Barrier

This problem is due to a lack of understanding of a very harsh reality: there is a relationship between the context and the tools (approach, framework, methods, etc.) you use. And the more complex the context, the stronger is the relationship.

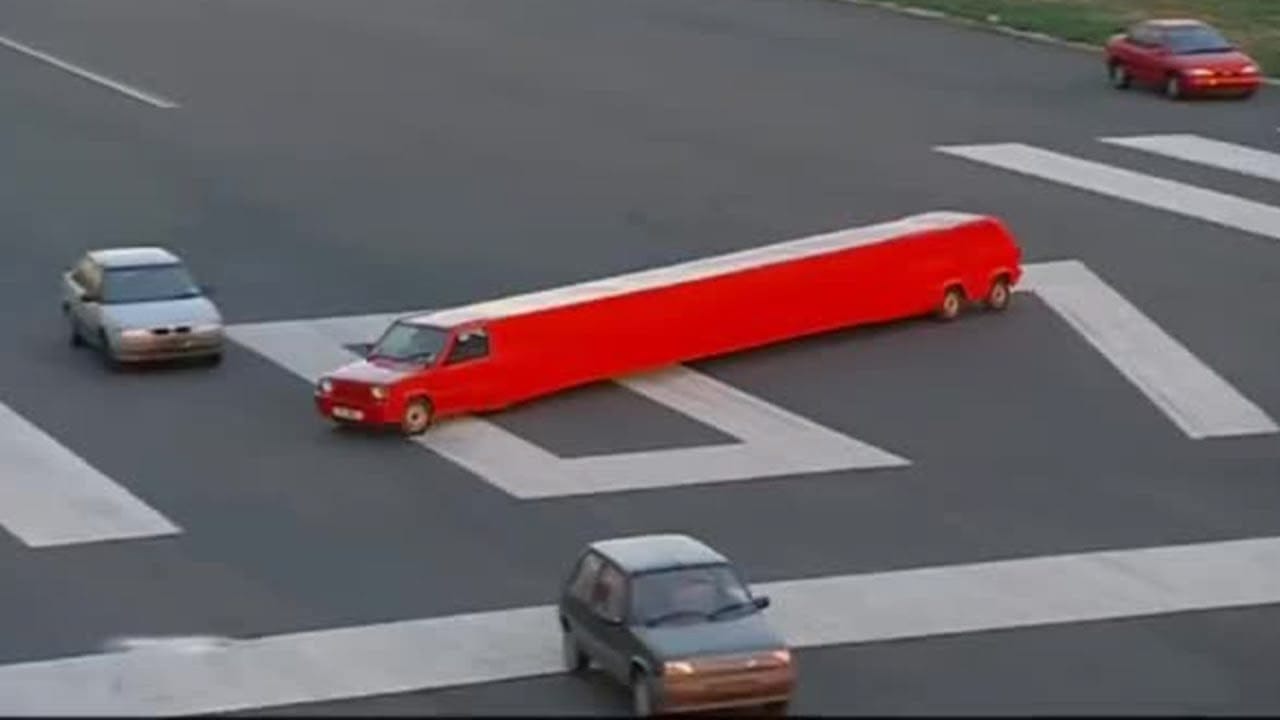

But another principle overlooked here is what I call the “space-for-action barrier”. Most of the time, when we work within companies or on specific projects, there is an assumed “space for action” on which either the project is based or the company expectations are built. This space for action is unconsciously determined by the type of outcomes, the “horizon” that a company is able to foresee. Narrow outcomes or not-so-far horizon means limited space for action.

These constraints against our ability to think and act are, most of the time, totally blind toward the complexity of the reality it evolves in! Unfortunately, their implications are huge.

The barrier happens when designers, innovators, or change agents try to redefine these constraints to make alignment with reality. Indeed, this barrier is the system’s immune response to change. As I said, this barrier impacts our ability to think, act, and therefore navigate: ignorance –or illusion of certainty– is sometimes preferable to some organizations.

Now does it mean that we always have to pass the barrier?

I don’t think so. We need as much “incremental improvements” as “deep & profound systemic change”. The question IS NOT to choose between linearity vs. non-linearity or reductionism vs. holism or simplicity vs. complexity. These are different ends to the same continuum! We probably need all of these to face future challenges. Now, place your cursors accordingly.

The only difference, to me, is maybe the actual awareness of organizations toward this reality. I will remain an advocate of mapping before picking the appropriate approach.

Conclusion

But to come back to the conflicting uses of Design Thinking and its related terminologies, my point with all of that is that all designers do not work at the same level of complexity. And necessarily the meaning, mental models, and concepts attached to terminologies are different.

I personally might have a very personal –or at least specific– idea of what “using” Design Thinking means. One that I share with some more or less recent tentative to make it evolve toward more a systems-oriented approach.

Is it the right definition? Well, with respect to the kind of challenges I try to tackle, yep. Do I have to impose this definition upon everyone’s definition? Nope. But I can surely disagree with –while understanding where they come from– if some try to use a definition for simple problems in a complex context (or vice-versa).

This reminds me of a recent discussion with Daniele Catanalotto about Planet Centric Design:

“You can redefine existing concepts to make them fit a new reality, or you can change the terms so that people understand that it requires a real shift in mind and worldview.”

Maybe we can do things better here?…

Beyond Human Centered Design

Is Planet Centric Design The Next Thing?medium.com

What are your thoughts on that?

This article was first published in Design & Critical Thinking.

References

- Kimbell, L. (2011). Rethinking Design Thinking: Part I. Design and Culture, 3(3), 285–306. doi:10.2752/175470811x13071166525216 (or read on sci-hub).

- GK VanPatter (2020). Rethinking Desing Thinking, Humantific & NexDesign Leadership Network.

- Donald A.Norman, Pieter Jan Stappers (2015). DesignX: Complex Sociotechnical Systems, The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation.

- Don Norman Keynote at Relating Systems Thinking and Design 4 Symposium, Systemic Design Research Network (2015).

Discussion