Following a recent discussion with Daiana Zavate on the ODD Owtcomes podcast about creating and perfecting our tools, and the publication of the book “The Discovery Discipline”, I wanted to share some thoughts on an issue we encounter frequently in the design, product, service, innovation (you name it) spaces.

A tale of misplaced faith

Back in 2016 when the book “Sprint: How to Solve Big Problems and Test New Ideas in Just Five Days” was published and the hype around the Design Sprint rigid process started to heat up, we could then read this:

Focusing on the surface allows you to move fast and answer big questions before you commit to execution, which is why any challenge, no matter how large, can benefit from a sprint. — Jake Knapp, Sprint (p. 28).

3 years later, along those lines, the narrative grew amongst the design community and many early adopters, who called themselves Sprint Masters, were now praising the supremacy and universality of their newly discovered tool. The Design Sprint was better, faster, stronger, and could solve any problem or challenge, no matter what it was. In 2019, I published a critique to investigate many of the bold claims promoted by both the book and the nascent design sprint community.

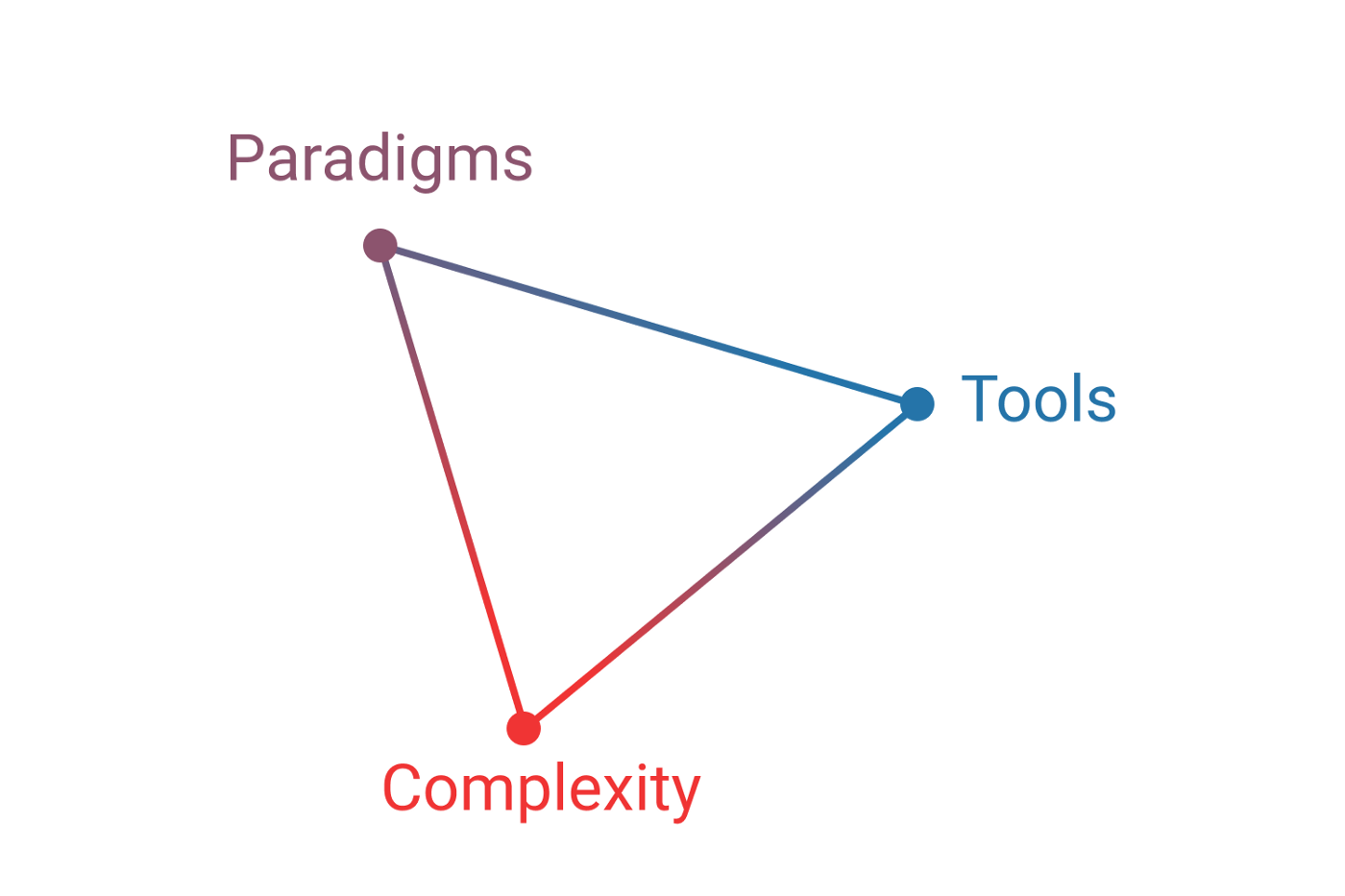

Complexity, Paradigms, Tools — The CPT relationship

Indeed, the problem was not the Design Sprint itself, but what people believed they could do with it: a misplaced faith in their tool.

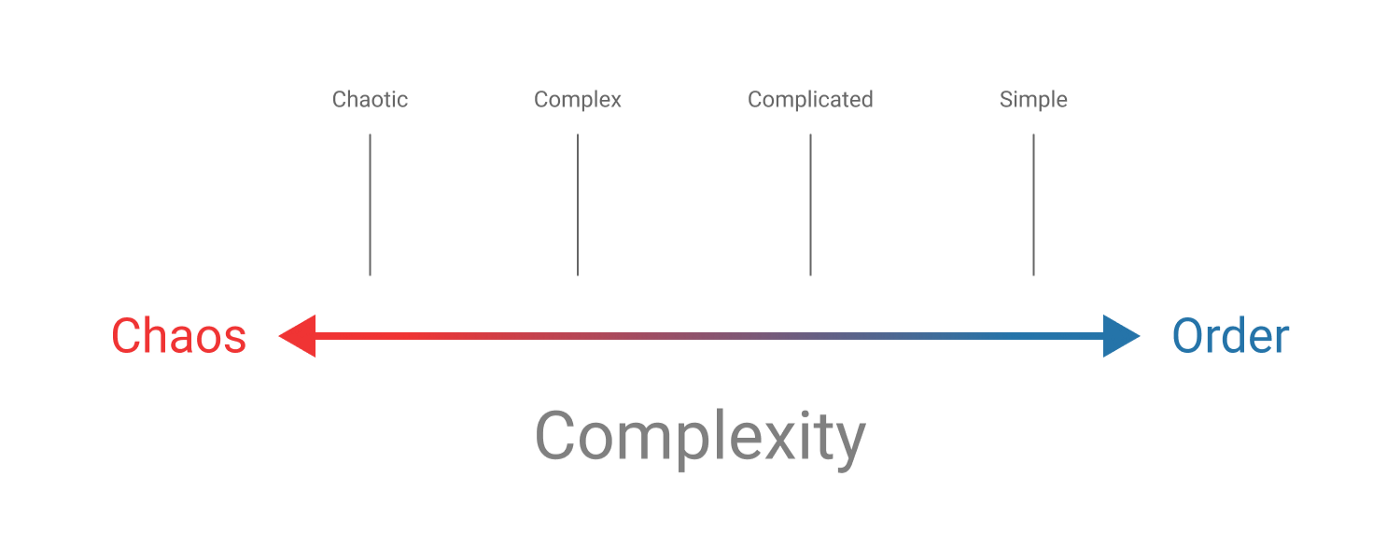

As I explored in this 2020 article, different contexts hold different intertwined states of complexity, and therefore there is a physical impossibility for any formalised tool or process to fit this inherent ambiguity/uncertainty without a high level of autonomy of the practitioners.

Interestingly, practitioners from various horizons have developed over time tools and paradigms to help them make sense and act within their environment. By looking at them from a complexity perspective, we can observe that some practices are better fitted for certain types of contexts [...]

This helps us understand the convergent and divergent aspects of the different paradigms and ideologies. We can now draw the interrelation between the complexity of a context (system), the tools, and the paradigms needed to tackle its challenges. – Kevin Richard, Innovation By Design: A complexity-based understanding and provocation.

Because of that, appropriation and adaptation to fit practitioners' local reality become a necessity. As I predicted in this article, the Design Sprint did indeed evolve until different flavours of it started to pop here and there: this is an unavoidable consequence of distribution within a network (see Network effect).

Where are we today? Well, a fringe of OG “sprint masters” truly believes in the original Sprint "by the book" to be the only true Design Sprint. Others have loosely adopted a version of it. Many others don't care anymore and moved on.

The false promise of universality through standardisation (fixation of rules)

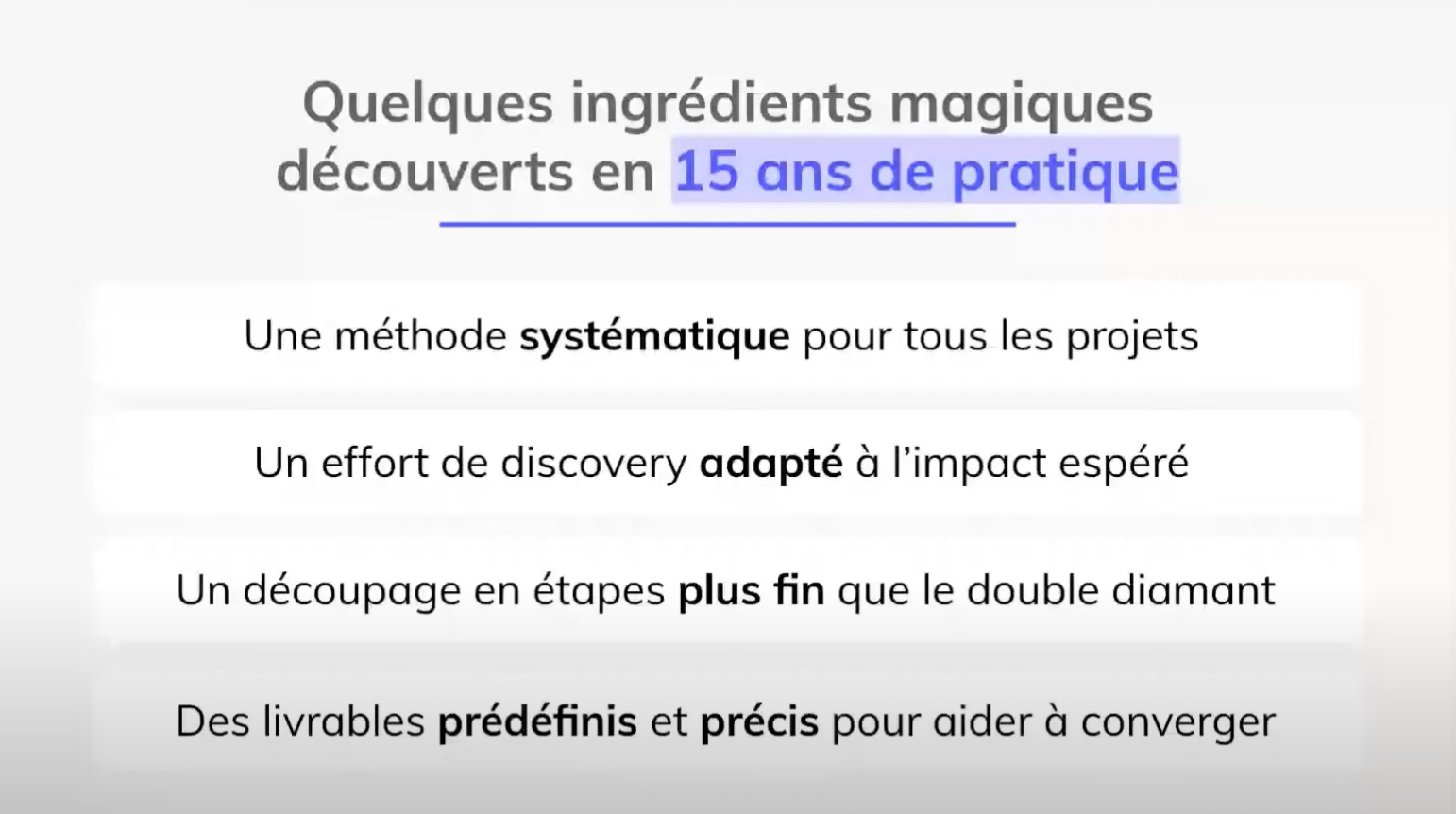

In their newly published book “The Discovery Discipline”, Rémi Guyot and Tristan Charvillat are quick to claim the necessity of imposing a systematic method, with clearly predefined deliverables, with the intent of “reducing uncertainty”. They assert that this makes their approach universal, regardless of the size or type of challenge you're facing.

Some magical ingredients discovered in 15 years of practice:

A systematic method for all projects;

An discovery effort that fit expected impact;

More fine steps than the double diamond;

Precise and predefined deliverables to help to converge.

Let's not ignore the fact that they use apparent credibility as a means to support their claim, making it clear from the start that they are both respectively Chief Product Officer and (former) Vice President of Design at BlaBla Car, one of the few (so-called) “french unicorn” startups. This surely means something, enough that the book was unavailable for several weeks because of high demand.

I can't avoid noticing a lot of similarities with the Design Sprint, both in the narrative and some superficial devices to display trust & credibility.

Whoever tells you that, universality through formalisation & standardisation of practice isn't a thing.

Bounded applicability

The basic concept of bounded applicability simply states that any method or tool has limits. You know you are reaching those limits as the cost/benefit ratio of handling new issues becomes adverse. At this point you should not carry on doing the established approach more furiously, but instead realise that you are approaching a boundary and gain perspective so you can look on the other side.

When we hear anything about making inmprovements to processes, technology, people, or tools - test if those suggestions have been placed in a bounded applicability. – source

Furthermore, bonded applicability is the concept that “different and contradictory things work in different bounded spaces”.

In his article Bounded Applicability & Conditionality, Lou Hayes reminds us of the importance of context conditions.

I've referred to this as conditionality. Conditions matter [...]

I recall a conversation with my son after a teacher complained he pointed a "finger gun" on the pre-school playground. (pew pew!) It was the start of teaching conditionality. Finger guns, NERF guns, and all other toy guns are allowed at home. But NO toy guns at school. Not even finger guns. (He's kept his finger holstered ever since.)

It makes sense to err on the side of safety and control. Safer to not touch anyone. Safer to not pet the dog. Safer to not climb the ladder. Especially since young kids might not comprehend the variables that go into the variety of "conditions" that can exist. So we come up with rules; sometimes ridiculous rules.

What complex adaptive systems (CAS) teach us is that those conditions are subject to changes (and sometimes, dramatic changes) over time, making the idea of a fixed, systematic, “universal” approach even more ridiculous.

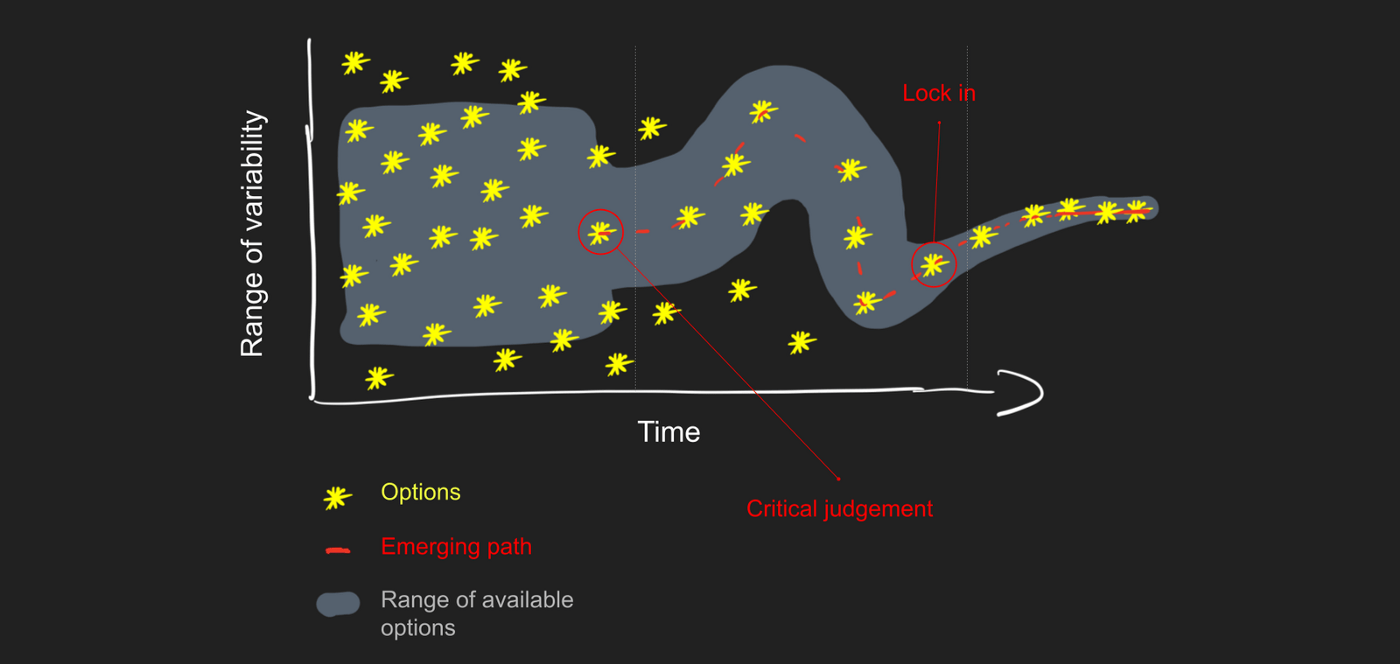

In my article “Organisation-wide design as systems practice” I explain why context conditions define opportunities (also called options) available to us at a given time. The path dependence theory describes how a convergent decision-making process leads to the reduction of opportunities over time.

Systematically aiming for funnelling down “problems” to one solution (see “Funnelling vs Layering”) that is supposed to fit many diverse contexts, understandings, and motivations is likely to lead at best to “premature convergence” (see here, here, and there).

In evolutionary algorithm, premature convergence means that a population (for an optimisation problem) converged too early, resulting in being stuck into a local minima or maxima state. This situation arise due to loss of diversity among individuals of the population. Techniques to avoid premature convergence is to maintain diversity among individuals of the population.

These concepts call for agility in our ability to sense, respond, and update our understanding of our context along the journey. More than a fixed, rigid, universal approach, discovery requires a huge dose of genuine curiosity (intrinsic motivation) and autonomy in our decisions, to derive from the set course because the destination (if it exists) isn't a fixed point on a map. More than discovery, we probably need exploration.

Thanks for reading!

Join our next session, join our Meetup group:

Join the latest discussion on Slack:

Help the community, make a donation:

Discussion