Rational Skepticism, Business, And Design.

Recently, I came across a video about Street Epistemology and it made me think about how we discuss the topic of design and user experience in organizations.

Specifically, if you ever been in a situation where you find yourself arguing against someone that is refractory to UX or HCD, we can sometimes land in a position where facing arguments that seem to us irrational (yet following its own well-constructed logic), we feel powerless and unable to elaborate proper or clear answers, even though we’re sure of the righteousness of our points.

In such situations, we may doubt at some point that we know what we know. But then, our natural tendency to cognitive biases will make us rationalize, and probably through a beautifully formed fundamental attribution error, make us keen to believe that the person was wrong and stupid.

Next time, I’ll be ready!

The rest of the story can easily end up in a fight, a polarization of the debate.

Without going so far in the extremes, a tiny amount of such behavior can lead to catastrophic communication issues.

Beliefs, opinions, facts, and methodology

What I often observe is that most people have beliefs (sometimes strong ones) about the users and how they behave, even tho these beliefs are contradictory or irrational.

On Myths & Beliefs in Business

3 Myths We All Have Been Taught And That Prevent You And Your Business To Growmedium.com

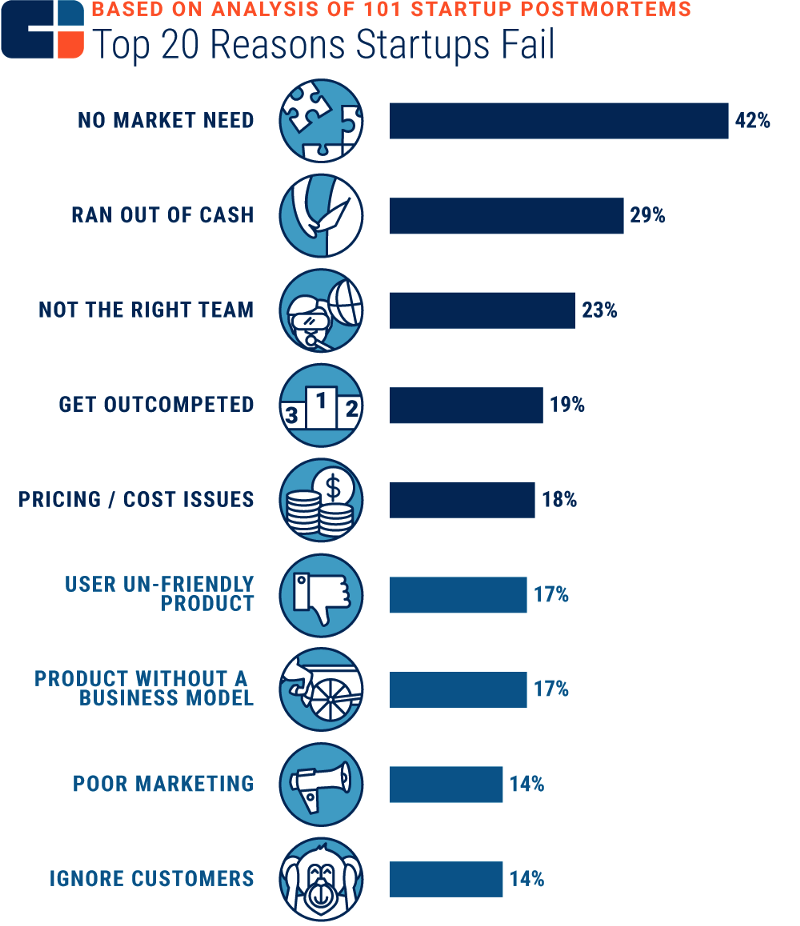

I also observe that Design and Business are often seen as places for (strong) opinions and acts of faith. You have to “trust your gut” in order to be “successful”, right? There are countless articles each year on this topic. The funny thing is to think of how many articles were not written about those “gut feelings” that didn’t lead to the expected outcomes. What a beautiful confirmation bias could that reveals, isn’t it?

If the only things to do in order to make your business or design successful is “trusting your gut” to have great ideas, then your opinion on the subject is not better than my grandmother’s one. In such a context, it’s clear that anyone is qualified to criticize your decisions. If you have nothing else than your belief to be right to bring on the table, you can’t really build something constructive from critics and debates.

In the same vein, people tend to believe what a particular group has accepted as true, even tho there nothing to back it up. These false beliefs spread due to our tendency to accept the established norms of our social group and environment. In business, it is well translated by the belief that “customers don’t know what they want”.

“If I had 1 hour to solve a problem I’d spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and 5 minutes thinking about the solution.” — Albert Einstein

If you have a clear and replicable methodology, people may criticize the result but you would have way more factual arguments to explain, justify, and prove it. And this is probably what can teach you critical thinking –and especially rational skepticism: making you care for the method that makes you know what you know, trust what you trust, and believe what you believe.

This approach helps you questioning your own reasoning, forcing you to verify and fact-check your arguments on a subject. This teaches you humility towards topics you don’t know. It makes you actively listening to other’s arguments, force you to check for reliable sources, and verify the arguments (yours and others) and eventually reconsider your position on the lights of new facts. It forces you to be aware of our cognitive biases and helps you sharpen up your capacity to detect fallacious speeches.

That’s what’s at the heart of the scientific method: building a proper understanding of the world surrounding us (knowledge), and improving it over time.

Prevent Sterile Debate

Street epistemology (SE) or epistemological interview can help you adopt a non-dogmatic, open-minded approach toward opinionated speeches and people.

This approach will make your interlocutor to explain the elements that lead to his opinion or belief, allowing you to highlight and question potential flaws in his reasoning as you ask questions, all this in a respectful way. The approach also has some similitudes with the “Four Whys” and the “user interview” methods in some regards. Anyway, by following some of its guidelines can help you become a better interviewer in general.

It is worth noting that this approach is iterative through a conversation.

A Step-by-step To Epistemology

1. Build rapport with your interlocutor

Build rapport with your interlocutor before getting deep into dialogue. Try to find something that you have in common.

2. Identify the claim

This step may involve idle chit-chat with the hope of chancing upon a worthwhile claim.

3. Confirm the claim

Confirm that you have understood your interlocutor correctly by summarizing and repeating their claim back to them. Don’t continue until you are both sure that you understand it clearly. If necessary, write down the claim so that you can both refer to it if the conversation goes off track.

4. Clarify definitions

If there are any words that are ambiguous (or potentially so) this would be a good time to nail them down with your interlocutor. Clarifying definitions is something that you may have to do multiple times as the talk progresses should it become apparent that you’re using words differently.

5. Identify a confidence level

Ask your interlocutor how confident they are that their claim or belief is true. If possible, have them put a number on it. If they are not willing or able to quantify it, accept whatever they give you and note that as their “initial confidence level”. For example, “How confident are you that “________” on a scale of 0 to 100?”

Note: The confidence scale is just a way of judging for yourself how much effect your efforts are having. It is optional and not an integral part of SE. Don’t persist, as doing so may annoy your interlocutor and be counterproductive.

6. Identify the method used to arrive at the confidence level

Ask your interlocutor how they have determined that their belief is true, or how they’ve arrived at their stated confidence level. They may provide multiple reasons. Try to focus on just one or two, ideally those that contribute the most to their confidence. Once you’ve settled on a primary reason or method, stay focused on that through the rest of the talk.

7. Ask questions that reveal the reliability of the method

Your main tools here are the Socratic method, the outsider test of faith (OTF), and questions that revolve around the falsifiability of their claims. Ask questions that, when answered, lead to a contradiction of your interlocutor’s assumptions or hypotheses.

8. Listen, summarize, question, watch, repeat

Listen to your interlocutor closely. Look at them directly and try to understand what they are attempting to convey without getting hung up on their exact word choices.

Summarize: Repeat what you think your interlocutor is trying to communicate and verify with them that you’ve understood them correctly. It’s important that they feel like they’ve been heard. It proves that you are being attentive and taking their beliefs seriously.

Question: construct more socratic questions.

Watch for those special moments where your interlocutor stops to “think”. This is often betrayed by the act of looking up at the ceiling, clearly trying to sort through things in their head. It’s important to detect these “aporias” and allow the silence to continue uninterrupted until the interlocutor speaks.

9. Wrap up the conversation

If your interlocutor previously offered their confidence level, ask them again as you wrap up. This can help you judge whether your dialogue had an immediate effect.

For example, “Given the things we’ve talked about, do you think your confidence level has changed? Do you still feel that 100% is accurate?”

Rules of Thumb

Pay close attention to your own demeanor. If your words, body language, or tone of voice betray even a small amount of condescension, your interlocutor will recognize this and be justified in reacting negatively to it. If your goal is only to “win”, and you don’t genuinely respect your interlocutor (even if you don’t respect their beliefs), then SE might not be right for you.

Most people new to Epistemology struggle to avoid being sidetracked when they hear clearly false, or unsupportable claims. They reflexively react to them by presenting opposing evidence or arguments. When you do this, you’ve gone off the rails. It’s not a disaster as you can just drop the point and get back on track, but it’s normal to struggle with this through many talks before you feel comfortable ignoring these things and staying focused on epistemology.

Don’t allow frustration to overwhelm you. Everyone is different.

Source: “Street Epistemology — The Basics”

What’s Your Methodology?

And you, what’s your methodology or approach to talking with such people in your work?

Other questions: Is “UX evangelist” a good definition in our context or a bit too dogmatic? Do you feel like a “UX believer”?

Thanks for reading!

Discussion