Hi, Kevin here.

We continue our exploration of Solarpunk and its relevancy to design (and designers).

From Uchronia to Dystopia, to Utopia

SteamPunk and DieselPunk are subgenres that are generally set in alternative historical timelines in which a certain technological aspect has been emphasised to the point of a foundational constraint which leads to various changes in society. These are called “uchronia”, a neologism for “alternate history” in the speculative fiction genre, to describe a story set in "no time" by analogy to a utopia, a story set in "no place" (Wikipedia, 2023).

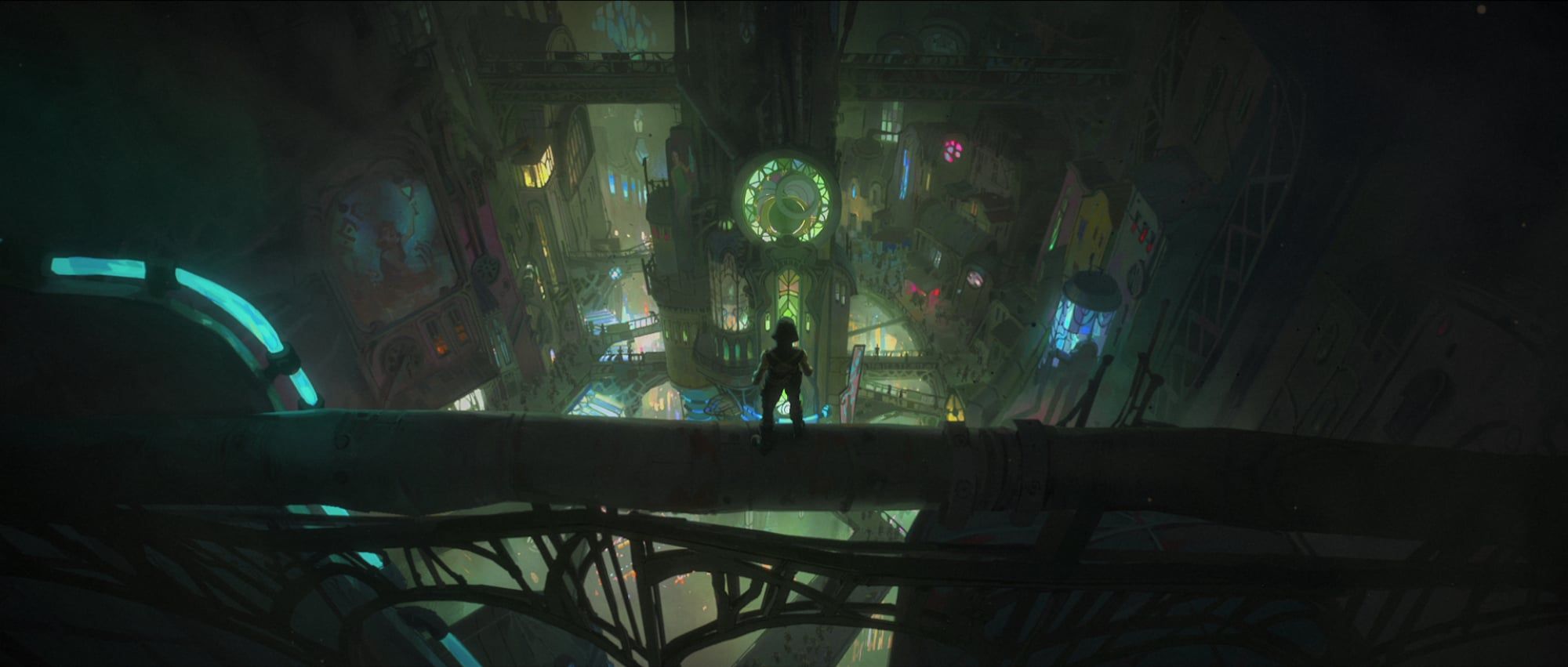

From “Arcane” the animated series – Netflix

They tend to display an anachronism in their aesthetics, playing with the notion of retro-futurism or “a future informed by past technology”. This is particularly evident with SteamPunk, which often set itself in an alternative future informed by the Victorian era aesthetic, technology of the late 18th and early 20th century and the advent of early industrialisation and automation of work through the mechanical power enabled by steam engines. SteamPunk is often presented as “optimistic retro-futurism”.

Left: “Paris” by an unknown artist | Right: “Lyonesse City” by flaviobolla

DieselPunk is often set in an alternative 20th-century era (the 1920s-1950s), or sometimes during the “interwar period” (between World War I - WWII), which therefore call for an “early modern war” aesthetic and Nazi imperialism imaginary: dark uniforms with tints of red, machine guns, gas masks, mass production of death and early signs of atomic weaponry. Because of that, DieselPunk is often presented as “pessimistic retro-futurism” compared to Steampunk.

Left: “Karl Ruprecht Kroenen” in Hellboy (2004) | Right: Sucker Punch poster (2011)

Importantly, they are objects of nostalgia and of idealisation of a past and a future (that never existed), which allows us to tell stories of the “now” through its distorting lens. A retro-future in which we would be bolder and the world bigger. A retro-future in which technology enabled through industrialisation is extremely capacitating and comforting (almost magical), and allows us to “tame the monsters and dragons of the world” as a metaphor of the uncertainties and unintended consequences we face today, subjugating them to our control through the power of [technology].

Two visuals from “Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow” (2004)

Interestingly, the two genres are bound to similar Western narrative points that are linked to the industrialisation of Europe, the advent of mass production and, with it, the reinforcement of certain ideologies and values about growth, energy and technology as a direct proxy for societal progress.

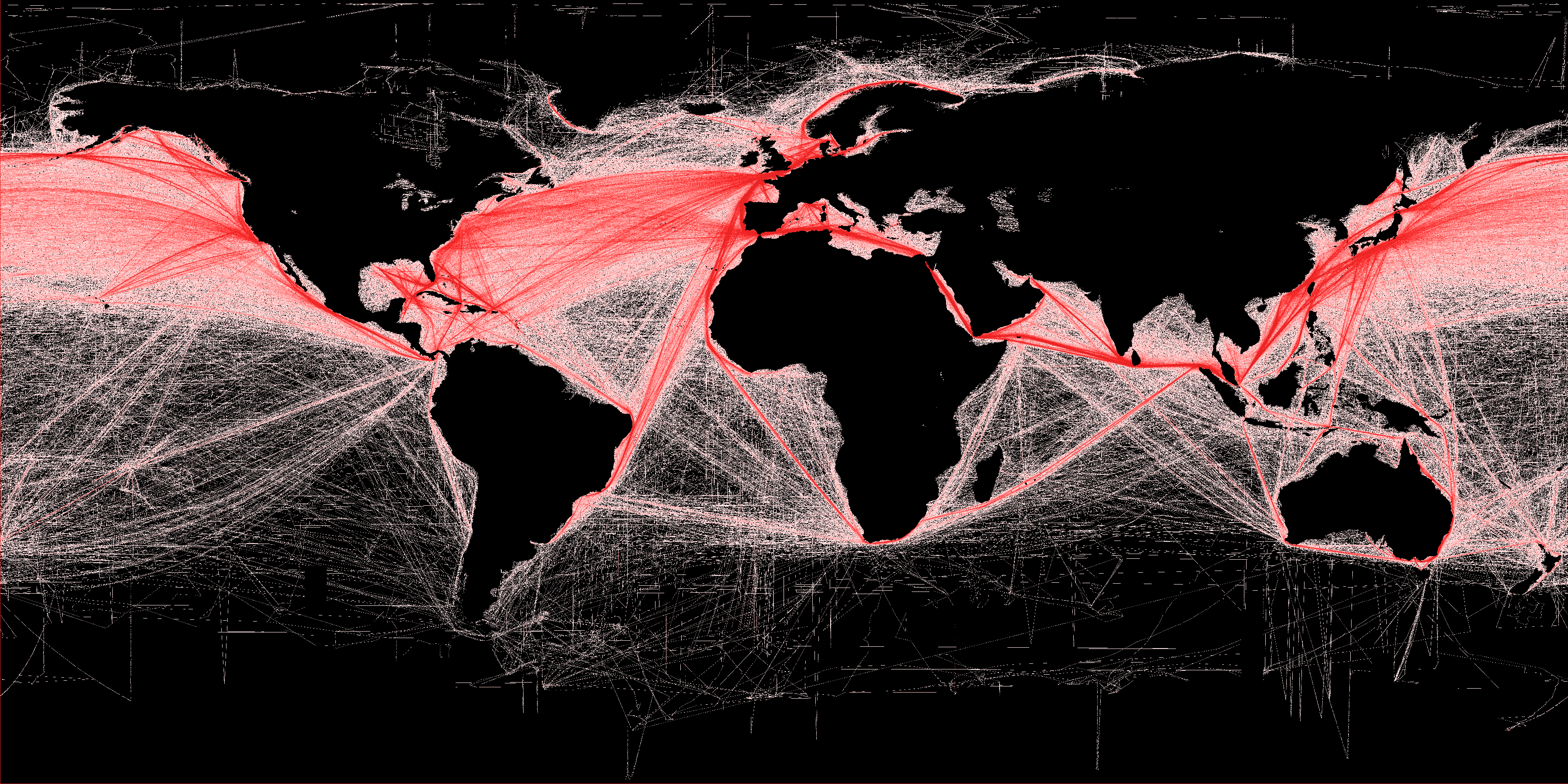

Although not directly connected in a linear fashion, CyberPunk emerges as a continuation of these narrative points: electricity, robotics, digital technologies, networks, artificial intelligence, hyper-connectivity, hyper-capitalism, globalisation and mega-corporations —and with these, a form of cultural homogenisation.

“The Matrix is a system, [and] that system is our enemy. But when you're inside, [what] do you see? [...] The very minds of the people we are trying to save. But until we do, these people are still a part of that system and that makes them our enemy. You have to understand, most of these people are not ready to be unplugged. And many of them are so inured, so hopelessly dependent on the system, that they will fight to protect it.” –Morpheus, The Matrix (1999)

Punk narratives –at least the good ones, some would say– have this interesting quality to question our relationship to the world, to nature, to others, and, ultimately, to ourselves. As a CyberPunk narrative, The Matrix (1999) is notably influenced by the work of Jean Baudrillard, a French post-modernist and post-structuralist philosopher, and his notion of “hyperreality”, a form of shared delusion which manifested through our means of control and power over the world: as technology becomes the desired way to interact with [reality] we become unable to distinguish reality from a simulation of reality.

“The Disneyland imaginary is neither true or false: it is a deterrence machine set up in order to rejuvenate in reverse the fiction of the real. Whence the debility, the infantile degeneration of this imaginary. It's meant to be an infantile world, in order to make us believe that the adults are elsewhere, in the "real" world, and to conceal the fact that real childishness is everywhere, particularly among those adults who go there to act the child in order to foster illusions of their real childishness.” – Baudrillard, "Simulacra and Simulations"

If CyberPunk narratives are often seen as dark (neon-style), depressing, dehumanised, and full of mega-structures and Archologies (Paolo Soleri, 1969) urban jungle visions of the future, they question what it means to be a human in an ever-connected, ever-amplified and ever-improved version of ourselves –to quote a well-known cyberpunk-inspired music group: “Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger”.

These narratives echo certain ideas that humans (and their cognitive abilities) and subsequently consciousness and life are analogues to computers. And these narratives are today almost ubiquitous and permeate the societal discourses about what technology, humans, and the future are about. This transition from “punk” to “mainstream” could be seen both as a loss and recombination of meaning, as it traverses various layers and boundaries of society: as Gilles Deleuze proposes, a process of “de-territorialisation” and “re-territorialisation”.

In many ways, because of that, the current techno-solutionist (and colonialist) culture mainly led by US-based companies (and figures), is stuck in paradigms from the 80s and 90s. In that respect, the kind of ideas very rich and powerful people are pushing forward, the likes of E. Musk and M. Zuckerberg or even Sam Altman (CEO of OpenAI), are still bounded and therefore limited to these paradigms —paradigms now deprived of their original meaning and reduced only to a certain form and appeal, used to sell exactly what CyberPunk was criticising.

Gilles Deleuze, another French post-modernist philosopher contemporary of Baudrillard and who shared some of his concepts, provides an interesting lens to view this narrative landscape. Deleuze, responding to the work of Michel Foucault –yet another French philosopher– explains back in the 90s that we shifted from what Foucault called “disciplinary societies” to what Deleuze call “societies of control”.

“What are societies of control?”, Jonas Čeika - CCK Philosophy on YouTube

Disciplinary societies are defined by physical spaces and the rules we are expected to follow within them. Disciplinary spaces are enclosures of time or space by some authorities or regulating bodies acting on behalf of a community or a group for instance –e.g. the role of a state. Being at work, in the street or at home means different expectations and rules constraining social behaviours. The workplace defines what “being a worker” means simply because it literally shapes and regulates behaviours. Following the rules bound to a given place guarantees social cohesion and order, hence “discipline” is an implicit social expectation of disciplinary spaces.

Societies of control, on the other hand, means that “you are no longer an individual or a member of a mass of individuals in a space that needs to be disciplined, now instead you're a dividual, which means you're a different source of information depending on which system you're interacting with. To a bank, you are your credit score; to a university, you are an SAT score; to your health insurer, you are your genetic risk factors; to YouTube, you are your watch history” (PlasticPills, 2020).

“Deleuze - Control Societies & Cybernetic Posthumanism”, PlasticPills on YouTube

In other words, Deleuze talks about control as a notion of “control checkpoints” and the removal of individuals’ autonomy through the deconstruction of their utility into neatly defined categories, with expected results and therefore expected value –from individuals to dividuals. The regulatory systems of societies of control, unlike disciplinary spaces, appear to provide more freedom and even over-abundance of choice and behaviours (i.e. individualism, personalisation, etc.), but this freedom is subjected and reduced to purely explicit and transactional interactions, mined for data extraction, reducing even further their utility and amplifying the loss of autonomy. Here the notion of control is not an end in itself but allows the fulfilment of the desire of the assemblages that we inhabit (products, services, groups, communities, etc.).

“Deleuze, Societies of Control“, Overthink Podcast on YouTube

Through this lens, we can see why the need for new utopias is palpable in many fields and spaces. SolarPunk seems to coherently blend many new and related narratives that arise in sub-cultures and fields that push for more sustainable, inclusive, equitable, and systemic changes. This is, in the light of Deleuze’s philosophy, an assemblage. Also, please note that there are other punk narratives emerging or recombining, like FusionPunk (see this Reddit for more FusionPunk). In most cases, they are about post-capitalist, post-growth, post-globalisation and post-cyberpunk societies.

Solarpunk narratives are a response (but not an answer) to the commodification of Cyberpunk tropes, to societies of control, to their explicit transactional nature, to our loss of autonomy, and to our environmental and societal challenges (and crisis)

Non-monolithic and proto-utopias

Solarpunk is a form of utopia as it is rather optimistic about some varying aspects of the future. But as with many punk narratives, it mainly offers a criticism of today's society, allowing us to reflect, nurture our collective imagination with new imagery, and pass the all-too-often cynical constatation of the shortcomings of our modern world.

In her recent interview, Monika Bielskyte, a Futurist and researcher, assert that utopias are by nature inherently exclusionary of minorities and marginalized peoples:

“Almost without exception, marginalized people are outright erased from all but the most recent utopian visions. Pretty much the only place where marginalized peoples exist in sci-fi and futurist visions have been in dystopias (and their presence is often perceived as a signifier of dystopia), because there's literally no place made for them in utopia, given the eugenic and exclusionary nature of utopianism.” – Bielskyte 2023, “Dangerous visions: How the quest for utopia could lead to catastrophe”.

But Solarpunk narratives are not simplistic or purely idealistic, but rather complex in their diversity. Borrowing from Deleuze, Solarpunk is an assemblage, not a monolithic utopia. I would argue here this is the reason why SolarPunk escapes (at least for now) Bielskyte’s categorisation. Moreover, I would be inclined to define SolarPunk as a “theme towards utopia” or even a “theme towards a better tomorrow” –in other words, an active unfolding process of decomposition and recomposition, not a static object/image.

Next week, we will investigate a topology of Solarpunk stories.

Thanks for reading!

Kevin from Design & Critical Thinking

Discussion