Yet another lengthy reply to Design Sprint proponents’ claims.

🔥 TL;DR;

The main claim is that the Design Sprint (Jake Knapp, Google) is a great tool for gaining a deep understanding of the problem context and users' motivations, if well executed. I reply that this not a matter of execution but goals and that it was never the point for the Design Sprint to gain a deep understanding of anything.

The Design Sprints' main goal is to move quickly from idea to materialization, with a minimum understanding of the problem, to validate it (the metric is speed), which make (kinda) sense in the context it was invented in (Google Ventures).

📝 Long reply

I reply here, in English, to an exchange with French podcast producers about Design Sprint, for which you can find below the specific video that triggered the discussion. I don’t feel like YouTube comments are a really good medium for long exchanges that requires developing a proper, richer, argumentation.

If you read/understand French, I invite you to watch the video and read the comments, as fair retribution for the time & effort put by its creators, and their kindness to reply to my criticism (I know, I can be a pain).

Anyways, I will translate the discussion here to give proper context, and try my best to reply point by point to their answer.

In preamble

Before going any further, here’s a short sidenote about the structure of this article, so you can navigate to what feels the most relevant to you. The article is divided into several main sections:

- The original discussion provides context to the exchange. I try also to expose my personal understanding and (necessary) assumptions about what we’re discussing.

- The rebuttal will dive deeper into the arguments provided and will be also divided into smaller pieces as we break down the latest (at the time of writing) reply from the creators of the Gommette — Design Sprint Podcast.

- Update after discussing with the two authors behind the channel.

- References contain links to resources that support, consolidate, and deepen my arguments. They can be found annotated like this [number] within paragraphs (For example, in the sentence “As explained in my article [1]”, “1” being the first item listed in the references).

Importantly, I will try to answer in the most respectful and intellectually honest manner: I’m talking about observable facts, quality of the arguments, soundness of the ideas, the applicability of the concepts, etc., but never about the persons.

Lastly, I have also to state that I have no direct conflict of interests. I don’t run an agency (nor am I a freelance) selling services directly related to the Design Sprint. I don’t personally know the authors of the method or any of their supporters/detractors, to whom I don’t share convergent interests or obligations. I’m, as far as I can, an independent practitioner, learner, reader, writer, and thinker, offering free & open reflections and critics (most of my writings are under Creative Commons) to help question, grow, and make sense of what we do (as designers, innovators, and changemakers).

Now, without further due, let’s dive in! 👇

Original discussion

For starters, and as often in such circumstances (namely, watching a video), I replied to something the guest of the show, Alexandre Koch, said about the process they apply at Servier (an international pharmaceutical group, to which A. Koch is responsible for the UX & Design Thinking pole).

It also has to be said that during the conversation, the speakers seem to make no noticeable differences between product design and innovation. We can assume, as it is suggested in the video, that they refer to the design process (and specifically the Design Sprint) as a means to “do innovation”, as it is commonly accepted in the product community — what I think is flawed and narrow reasoning for all the reasons explained here.

So, my comment addresses what A. Koch said at 42:12 of the video, but reflect some contention points I have with the whole discussion here, namely the too often conflation and equivocation of many things as if equal or interchangeable.

“starting with the field data” […] “like Jake Knapp in his book”… Sorry but, even if we can agree with the first point (and yet, we rarely start from a blank slate), hard to see how it relates to what Jake proposes.It is rather the opposite, since he generally offers to skip the research phase (as explained here → https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c7K3ubQw3XA ).

Moreover, if we talk about “data-driven design”, the design sprint is neither a good starting point, nor a suitable framework (sampling bias, selection bias, group effect, etc.).

Guys, I know your podcast is all about design sprint, but it would be nice if you invited more critical people on the topic. It’s been a while since I wanted to do an episode “Design Sprint: the good, the bad, the ugly” …

Anyway, well done for this episode! 👏👍

Soon after I hit the “send” button, came a reply from the channel author(s):

Hey Kevin, thanks for your comment and the link to the video! We agree with you, if you follow Jake (and others), the strength of the Design Sprint is to be able to work without field research, because they start from the assumption that if your sprint team selection is good, then each of the sprinters have some of the necessary and sufficient data to start a sprint.In addition, if you consider that the objective of the research is to properly know the context, the needs, the motivations, and the pains of the users, then a Design Sprint is an incredible research device in itself, since the learning curve is huge in 5 days (between user interviews on the first day, and user tests on the last day).

The video you share reminded me of another article written by Jonathan Courtney in 2017 on the subject: User research is overrated → https://medium.muz.li/user-research-is-overrated-6b0fe101d41

This being said, it is clear, not without reason, that many Sprint Masters also like to secure their Sprints by carrying out a research phase upstream of the sprint in order to supply the team with solid inputs.

It appears to me that there was a misunderstanding in my remarks that lead the author to think I was giving credit to the affirmation that “the Design Sprint allows you to skip research” or “is a good research tool” itself. I tried to clarify my point as follow:

Thank you for your answer Gommette — Design Sprint Podcast 👍With all regards, the design sprint has undeniable values, but not that of doing research. The speeches made by people like J. Courtney are mainly to sell their services. To say that research is useless is simply to 1) make people talk about it; 2) to comfort those who find it tedious & complicated that, really, in fact, it’s not their fault.

I wrote a fairly thorough review on the subject of design sprint and these “selling arguments” back in 2019 → https://medium.com/human-centered-thinking-switzerland/a-critical-analysis-of-the-design-sprints-argumentation-e4a2753dd873

BTW, my review is not a black & white argument. It’s about understanding the purpose of what you are doing. If we want to quickly move towards a digital product and therefore necessarily assume, from the outset, that we know how to respond to the problem (namely, a product), that we mindful on the fact that we will filter information on that basis, then the Design Sprint is perfectly suited.

Anyways, looking forward to discussing this with you.

In the meantime, I contacted one of the creators of the channel through LinkedIn to explicitly propose a one-to-one video call to discuss it further, as I felt the conversation (already) limited by the medium (aka the YouTube comments).

As such, my answer is not particularly good at providing what I believe are the necessary arguments to support my point, and I clearly heavily relied on my article to give weight to it without putting much effort — lazy me!

Anyways, a few days later I have been notified by YouTube that someone at Gommette — Design Sprint Podcast (the YouTube channel) replied to my comment. The same day, I received confirmation for our video call.

Kevin Richard, thanks for sharing your article that I already knew about. However, I am more mixed on the answer, and I would like to say: yes and no :)If the objective of user research is to better understand the contexts, the deep motivations and the difficulties of the users to guide the design process, then from experience I have no doubt that the Design Sprint, well executed, can be a relevant research method.

In 4 years of practice, I have observed that the learning curve of my clients in knowing their users has exploded like never before the Design Sprint came along. In the worst case scenario, they’ve at least learned that they don’t know anything and now need to take user research seriously. And it’s not uncommon for clients to take on post-sprint research assignments.

Why ? Because the Design Sprint is already simply a great opportunity to bring together the clients and their users. This causes, at the very least, an extremely strong awareness of the need to integrate users into the Design process, and it is an essential prerequisite.

In addition, users are not necessarily invited only at the end of the Sprint. Depending on the needs and necessity, they can be invited from day 1 to be interviewed by the Sprinters, and they can, if it is relevant (as in the case of the design of business tools for example), be invited to join the Sprint team. In this case, over 5 days we have 3 methods of collecting user insights. It’s huge.

This does not mean it is perfect, that it is sufficient on its own, and that it does not convey any bias (and on that I fully agree with you in what you say in your article), but NO data collection techniques (quantitative or qualitative) can pretend this neither.

Observation, interview, focus groups, quantitative analyzes … all these techniques, without awareness and master of their advantages and their limitstions, can lead to erroneous learnings, leading to dramatic design decisions.

It is the responsibility of Sprint Leads to make clients understand the advantages and limitations of this approach.

Rebuttal

1. 1 Scope, knowledge, and agency

If the objective of user research is to better understand the contexts, the deep motivations and the difficulties of the users to guide the design process, then from experience I have no doubt that the Design Sprint, well executed, can be a relevant research method.

First, I’m wondering what would be the objective of user research except, precisely, a better understanding of anything user-related.

Anyways, this is not a matter of “good execution” but goals: a wrong method, well-executed, remains a wrong method. The goal of the Design Sprint is to rapidly materialize an idea and test it with a minimum understanding of the problem. We test an idea against users' feedback, to validate it, and through which we will retrieve data to improve/modify/refine the idea. The focus is on the idea and its materialization, and the instruments are centered around this goal (i.e. about 2/3rd of the sprint is about generating and selecting an idea).

The goal of the research varies depending on how much we know about the context of a problem/challenge or how far we are in articulating ideas to act against this problem/challenge.

What we generally mean by “research” is, to simplify, exploring the problem-space, as opposed to the solution-space (although, I find this formulation reductive), and for which we more commonly refer to “testing”.

At this stage, research is about learning information, meaning, values, etc. (what we can call relationships) about the users and their environment (not test ideas), generally by using a combination of methods to mitigate bias (because what people say isn’t enough) and gain different levels of understanding — something largely absent from the Design Sprint.

As explained in my article [1], research requires adaptability because, unlike the Design Sprint, we want to adapt to the context (the reality) rather than forcing reality into our process — and say, create fake consensus because of the group dynamics.

If you really want to formulate it this way (mental gymnastic), the Design Sprint might be a research method, but nothing is made to gain a deep understanding of anything — which is unfortunate for a research method. Because of the sheer time spent on gaining understanding and reflect it, it is surface-level research at best.

The Design Sprint process cannot solve "big problems" or lead...

The Design Sprint (DS) is a 5-day process that promises to "answer any teams, companies, and organizations' challenges"…www.kialo.com

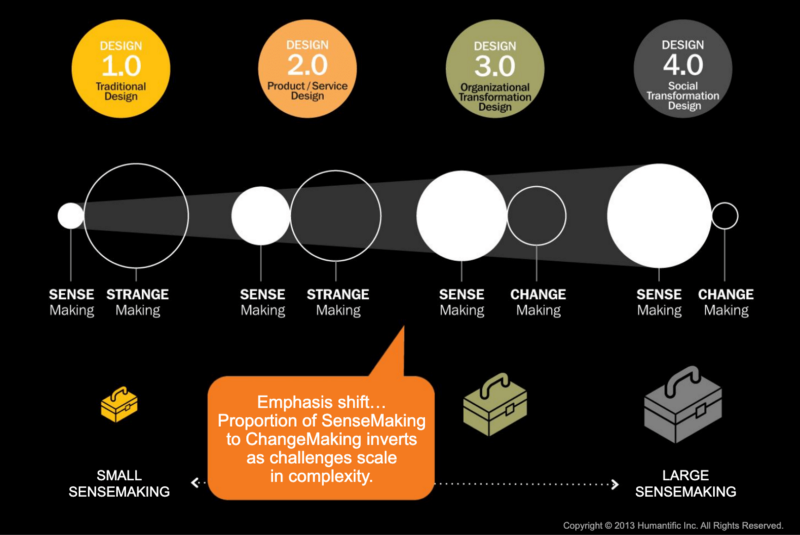

By the way, this surface-level and narrow focus fits well (in terms of thinking style) with what the design sprint is made for: single-point solution, digital products (see graph below).

Now, as stated in my article [1], this is not necessarily a big issue: all challenges don’t require tons of research beforehand. But it has to be acknowledged that a narrow understanding (few interviews on day one fit this description) leads to narrow outcomes. This is something well-accepted by a majority of experts in the fields of sensemaking and design for complex challenges [2][3][4][5], and to some degree, even by people like Alex Osterwalder [6].

1.2 Design Sprint as a probing device? Not quite it.

Probing is about learning from the field, by the field. We create mediums to gather stories in context to gain a multi-layered understanding of the relationship between people & the context. It’s about facilitating for the emergence of patterns of coherence [7] and so using methods that fit well with unpredictability and adaptability.

1.3 Design Sprint as a safe-to-fail experiment? Not quite it neither.

Safe-to-fail experiments are characterized by:

- Their continuous, on-going nature. Design Sprints are one-shot;

- Their ability to demonstrates intended impacts (or lack of)[8], which requires parallelization (see hawthorn effect [9]) and triangulation (diversity of methods) [8]. Design Sprints are linear, out of context, and lack proper evaluation criteria (see below).

1.4 About goals & evaluation

None of the claimed values & goals of the Design Sprint (ya know: team alignment, team learning, increase likelihood of “product success”, etc.) are measured by the method anyway [10]. What the Design Sprint “measure” is the usability of the solution and what people say they “like” and what they say they would do (i.e. buy and/or use the solution) — all of these are spuriously correlated by Design Sprinters to the “potential success” of their so-called “innovation”.

1.5 A definition problem

Design Sprinters largely assumes that “product creation” is synonymous with innovation. This belief is heavily inferred by the Design Sprint creators and the philosophy they subscribe to [11]. This idea & reduction of “innovation” to a neatly defined “product” is indexed to (and limited by) the idea in economics that (societal) innovation & growth necessarily comes from products competing on a free market and the idea that “good products” succeed based on their sole inner qualities [12]. This is questionable and criticized because (to simplify) it assumes the objectivity & rationality of the agents [13], doesn’t take into account the dynamics of complex adaptive systems [14][15][16], and excludes other forms of innovation [17][18][19][20][21].

1.6 A framing problem

This goes hand & hand with the previous point. Design Sprint heavily predetermines the type of results you’ll get at the end (i.e. a digital product) — which makes sense in the context it originated from (Google Ventures) but doesn’t fit for any type of challenges (despite what the book suggests) [1].

This implies a lot of things upstream, amongst which the framing and filtering of the context (its reduction) to fit the process [22], regardless of what the context actually is and what it might truly necessitate in order to change (positively).

Research, especially sensemaking methods, is meant to prevent such context-response misalignment, which has the potential to create more problems.

2. Levels of evidence & appeal to personal experience

In 4 years of practice, I have observed that the learning curve of my clients in knowing their users has exploded like never before the Design Sprint came along. In the worst case scenario, they’ve at least learned that they don’t know anything and now need to take user research seriously. And it’s not uncommon for clients to take on post-sprint research assignments.

Personal experience seems to be used as an argument here, but this is not enough [23][24]: it is easy to come to contradictory conclusions through personal experience, and I could argue against your position from my experience, it won’t help move the discussion further — this is a dead-end.

But let me ask some basic questions (looping back to evaluation criteria):

- The Design Sprint is good compared to what?

- Against what do you measure your clients’ learning curve? (see Survivorship bias [25])

- All of these are feelings and personal testimonies or do you actually have evidence to support your claim? Could there be other factors at play in what you observe?

- On a scale of 1 to 10 (1 being I’m not confident at all, 10 I have no doubt at all), what’s your level of confidence?

Also, we can observe that Design Sprint proponents love to talk about “evidence” but often relies on the same appeal to personal experience, their clients’ satisfaction (which tells nothing about the DS qualities), and other spurious correlation to prove their point. [34]

The leading figures of the Design Sprint are keen to make “proofs” and “evidence” out of thin air using rhetoric, claiming all sorts of miracles, but let's not forget where the burden of proof lies [26]. Let’s not forget neither that these people have something to sell: design sprints (see motivated reasoning [27]).

Then we have examples like this [28], from one of these people well-served in selling Design Sprints [29], that demonstrates how far they are from understanding what “research” or “evidence” exactly are [34]👇

The Truth About the ROI of Design Sprints: Primary Research Findings

Ever since Jake Knapp released Sprint in 2016, the methodology has only been rising in popularity! Every day, more and…www.linkedin.com

There is more than one issue with this so-called “study”, and I think this tells a lot about the epistemological crisis in which the Design profession is. Anyways.

Again, the Design Sprint is a heavy assumption-boxed paradigm: from the beginning, it assumes the solution must be a digital product. The process then forces reality (the people, the context) into a rigid, ultra-guided approach to producing the predetermined result. This frames everything and especially what type of understanding your clients have about their users and the types of outcomes/impacts they can generate (see path dependence [30]).

Talking about evidence, we can look at the numerous case studies published to notice a pattern: without modifications, a design sprint produces mainly narrow digital solutions [31][32][33].

3. What works is not specific to the design sprint

Why ? Because the Design Sprint is already simply a great opportunity to bring together the clients and their users. This causes, at the very least, an extremely strong awareness of the need to integrate users into the Design process, and it is an essential prerequisite.

Oftentimes, the advantages claimed by Design Sprint proponents are not specific to the approach [35].

Firstly, I can argue about the same thing with other approaches that present fewer environmental constraints and better integrates with most organizations. This does not make a particularly strong argument in support of the Design Sprint.

Secondly, things like convergent/divergent thinking practices, time constraints, putting everyone involved in solving a problem together, are not magical nor new. Practices like CPS (Creative Problem Solving), for instance, do that since the 30s [36]. Understanding when to use them, however, is important. Over-stressing time constraints and convergent thinking along the entire process is certainly far from being a smart move and certainly has an impact on the outcomes.

4. Reduction by the lowest common denominator & equivocation fallacy

This does not mean it is perfect, that it is sufficient on its own, and that it does not convey any bias (and on that I fully agree with you in what you say in your article), but NO data collection techniques (quantitative or qualitative) can pretend this neither.

What you’re implying is misleading. This is not because all methods are not totally absent of any bias that they are all equal in all circumstances.

As already discussed here, goals matter: a “bias” is relevant in terms of relationship to the context, our level of knowledge/understanding, etc.

Again, balancing methods & technics to mitigate bias is at the core of research: something the Design Sprint cannot pretend to because it is rigid in its conception.

5. Responsibilities & consequences

It is the responsibility of Sprint Leads to make clients understand the advantages and limitations of this approach.

Okay, but this poses an issue because Design Sprinters are often external to the organization, an organization that has to live with and remain accountable to what was released to the world.

This is also problematic because as a Design Sprinters who sells Design Sprints and who is potentially known for that (something clients expect from you), you don’t necessarily expose all available options to your clients (see availability bias [37]). Especially if you think that the Design Sprint is a relevant research tool.

Update after discussion

Since I posted this article, I had the great opportunity to discuss with the two authors behind Gommette — Design Sprint Podcast. It was interesting and allowed us to contextualize better the original discussion and clarify some misunderstandings.

First and foremost, I want to clarify that my criticism here is about the (limited) exchange we had in the comment of the video (not the video itself nor the position of their guest A. Koch) and specifically on the argument “the design sprint is a relevant research method”, with the context available to me at the time of writing. At no point, it was my intention to misrepresent or reduce the whole position of any of my interlocutors — although they had the feeling I polarized their position.

I stand for what I said here because my intention was not to demonize anyone but to articulate my thoughts and generate a discussion. It has indeed to be acknowledged that Gommette authors’ position should not be reduced to what is discussed here.

Thanks to their open-mindedness and positive attitude, and thanks for reading.

References

- Kevin Richard, “A Critical Analysis Of The Design Sprint’s Argumentation”. Design & Critical Thinking medium publication, 2019.

- GK VanPatter, Elizabeth Pastor, and Peter Jones Ph.D., “Rethinking Design Thinking”. Humantific, 2020

- David J. Snowden, Cynefin Framework. Wikipedia.

- Daniel Schmachtenberger, “The War On Sensemaking”. Rebel Wisdom production, 2019. Find an article version here.

- Enterprise Design Pattern, Intersection Group 2020.

- Alex Osterwalder, Yves Pigneur & al., “Value Proposition Design”, Strategyzer 2015.

- David J. Snowden and Mary E. Boone, “A Leader’s Framework

for Decision Making”. Harvard business review, 2007. - Introduction to Safe to fail experiments, NHS ACT Academy.

- Hawthorne effect, Wikipedia.

- Cameron Norman, Design’s Accessibility Problem. Censemaking, 2021.

- Kevin Richard, “The Ethics of Design Sprint”. Design & Critical Thinking publication, 2020.

- Kevin Richard, “The Innovation Washing Machine”. Design & Critical Thinking publication, 2021.

- Homo economicus, Wikipedia.

- Complex Adaptive Systems, Wikipedia.

- David J. Snowden, “The Apex Predator Theory” (video). Find also this article “Evolving Naval Safety: An Apex Predator Approach” AGLX, 2019.

- Greg Satell, “It’s Ecosystems, Not Inventions That Truly Change the World” 2019.

- Kevin Richard, “Innovation by Design: A complexity-based understanding and provocation.”. Design & Critical Thinking publication, 2020.

- Sitra Lab, “Orchestrating Innovation Ecosystems (and Portfolios) for Transformation”. Sitra the Finnish Innovation Fund, 2020.

- What is Systems Innovation?

- Social Innovation, Wikipedia.

- “Re-thinking Public Innovation, Beyond Innovation in Government”, Dubai Policy Review 2020.

- Enrique Martinez, “16| Framing”. 750 max. publication, 2021.

- Appeal to personal experience, YourLogicalFallacyIs.

- Anecdotal evidence, Wikipedia.

- Survivorship bias, Wikipedia.

- The burden of proof, Wikipedia.

- Motivated reasoning, Wikipedia.

- Amr Khalifeh, “The Truth About the ROI of Design Sprints: Primary Research Findings”. Published on LinkedIn, February 2020.

- AJ&Smart's Youtube channel displays tons of videos praising the Design Sprint merits.

- “Path dependence is when the decisions presented to people are dependent on previous decisions or experiences made in the past.” — Path Dependence, Wikipedia.

- A list of Design Sprint case studies, published by Design Sprint Stories.

- “Rebuilding a fitness app after COVID with a Design Sprint”, Sprint Stories 2021.

- “Are Design Sprints Worth It? A case study on how the government leveraged Design Sprints for public safety”, published on UX Planet publication, 2020. 👉 Yet another example of what the design sprint is good for: the ordered domain of complexity, where there are little-to-no unknowns (all of them being knowable with a bit of method anyway) and where you already have a pre-determined solution for a pre-determined result (simple causal relationship).

- A rough guide to the types of evidence, Compound Interest 2015.

- Kevin Richard, “Is Design Sprint A Necessity?”. Design & Critical Thinking, February 2020.

- GK VanPatter, Elizabeth Pastor, “Innovation Methods Mapping: De-mystifying 80+ Years of Innovation Process Design”. Humantific, 2016.

- Availability bias, Wikipedia.

Discussion